Most food companies track their Corporate Carbon Footprint (CCF). But on its own, that total says little about where emissions are coming from or what to do about them.

The problem is Scope 3. In the food sector, it often makes up more than 80% of total emissions. But it’s typically calculated using industry averages or spend-based models. These methods are fast, however, they blur the real differences between suppliers, ingredients, and production methods. The result is a footprint that meets reporting requirements but lacks the detail to support real decisions.

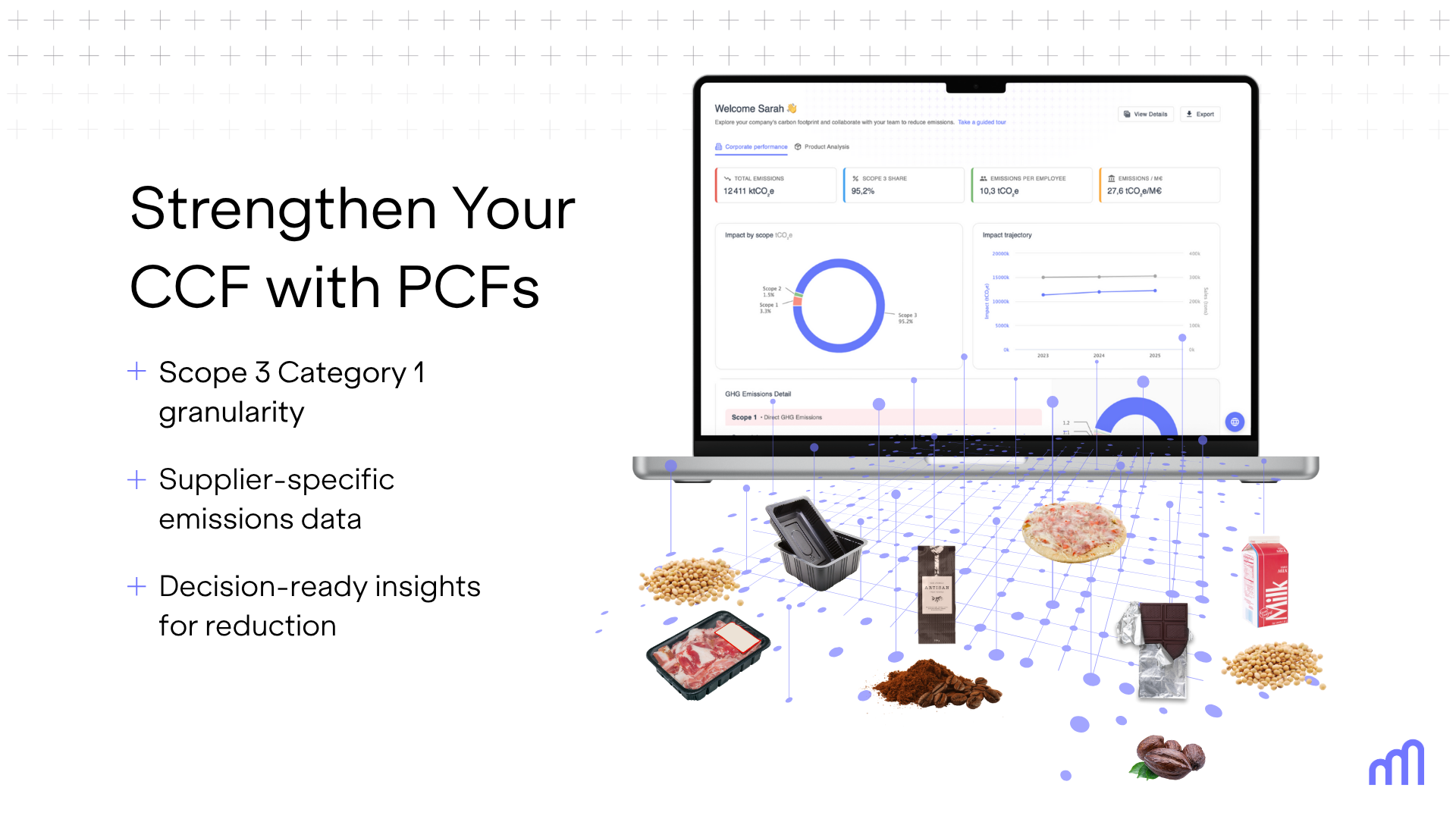

Product Carbon Footprints (PCFs) give you that missing detail. They break emissions down at the level of individual products and suppliers, making Scope 3 more accurate and actionable.

In this article, we’ll look at how PCFs can strengthen your corporate carbon footprint, surface more precise reduction opportunities, and help you meet growing data demands from regulators, investors, and buyers.

Your Corporate Carbon Footprint accounts for the total greenhouse gas emissions tied to your company’s activities over a reporting year. That includes direct emissions from your operations (Scope 1), emissions from purchased energy (Scope 2), and indirect emissions across your value chain (Scope 3).

Product Carbon Footprints zoom in on individual products. They track emissions from raw materials through to end-of-life, using data specific to how each product was made.

The link between the two lies in Scope 3. In particular, PCFs improve the accuracy of reporting in Scope 3 Category 1: Purchased Goods and Services. For most food companies, this is the biggest and most complex part of their footprint.

Generic methods like spend-based or industry-average estimates miss important differences between suppliers. PCFs use supplier-specific data to reflect actual practices, giving you a more granular view of upstream emissions.

This shift, from rough estimates to granular data, makes Scope 3 reporting more reliable and decision-ready.

The next section breaks down how to apply PCFs in Scope 3 calculations: what data you need, how to structure it, and how to make it count.

The GHG Protocol allows three methods for calculating emissions in Scope 3 Category 1 (Purchased Goods and Services):

Most companies rely on the first two because they require less data. But these methods rely on generic values that don’t reflect real differences between suppliers, regions, or production practices. The result is an estimate that’s often too broad to be useful.

PCFs use the third method. They draw on supplier-specific data, such as how a product was grown, processed, packaged, and delivered, to reflect actual conditions in your supply chain. That gives you a more accurate view of emissions tied to what you purchase.

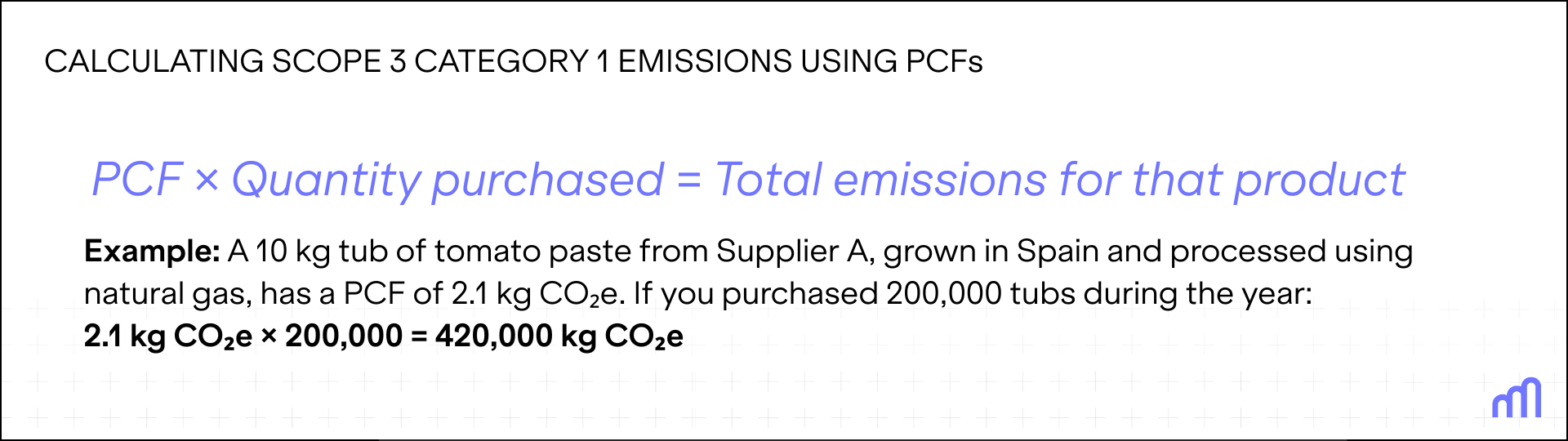

To apply PCFs in Scope 3 Category 1, you need two inputs:

Once you have that, the calculation is straightforward:

Unlike spend-based or average factors, PCFs directly reflect your specific supplier and sourcing choices. This means that a change in supplier, country of origin, or energy source will directly impact the calculated footprint. This level of precision is invaluable for identifying the true drivers of emissions and pinpointing effective areas for action.

The hybrid method offers a pragmatic yet powerful solution, and it’s the approach Carbon Maps champions after the supplier-specific data approach, which often proves to be a significant challenge.

The hybrid method strategically combines the most granular supplier-specific data you can gather with expertly matched secondary data to fill in any missing information. This means you still leverage the most granular details available from your suppliers, while ensuring you have a comprehensive and reliable estimate even when complete primary data isn't feasible. The hybrid method, therefore, stands out as the most accessible and practical path to achieving high-precision, actionable insights into your Scope 3 Category 1 emissions.

Using PCF data for Scope 3 Category 1 calculations gives you:

Measuring product-level emissions is only the first step. The next is knowing where to act. Food companies are using PCFs to move from broad totals to clear, targeted decisions. Here’s how they’re putting that data to work.

Without product-level data, companies often focus on what’s easiest to change. Packaging is a common example. It’s visible, measurable, and relatively easy to modify, but it’s not always the biggest source of emissions.

PCFs highlight where emissions are coming from, across products, ingredients, and recipes. This helps teams focus on the changes that matter most.

PCFs make eco-design pragmatic. By modeling the emissions impact of different ingredients, suppliers, or production methods, teams can compare options before making the final decision. This helps teams weigh emissions alongside cost, taste, and nutrition, and make informed trade-offs before the product goes to market.

PCFs link emissions to specific products and suppliers. This helps procurement and sustainability teams identify which suppliers are contributing most to Scope 3 emissions and where to focus first.

Linking PCFs to your CCF turns product-level data into a more detailed view of your company’s emissions. It helps you identify high-impact products, prevent double counting, and improve how emissions are assigned across Scopes 1, 2, and 3.

Here’s how to do it properly.

Make sure your PCFs and your CCF are built on compatible methods:

Using consistent methods makes it easier to connect and consolidate data across your footprint.

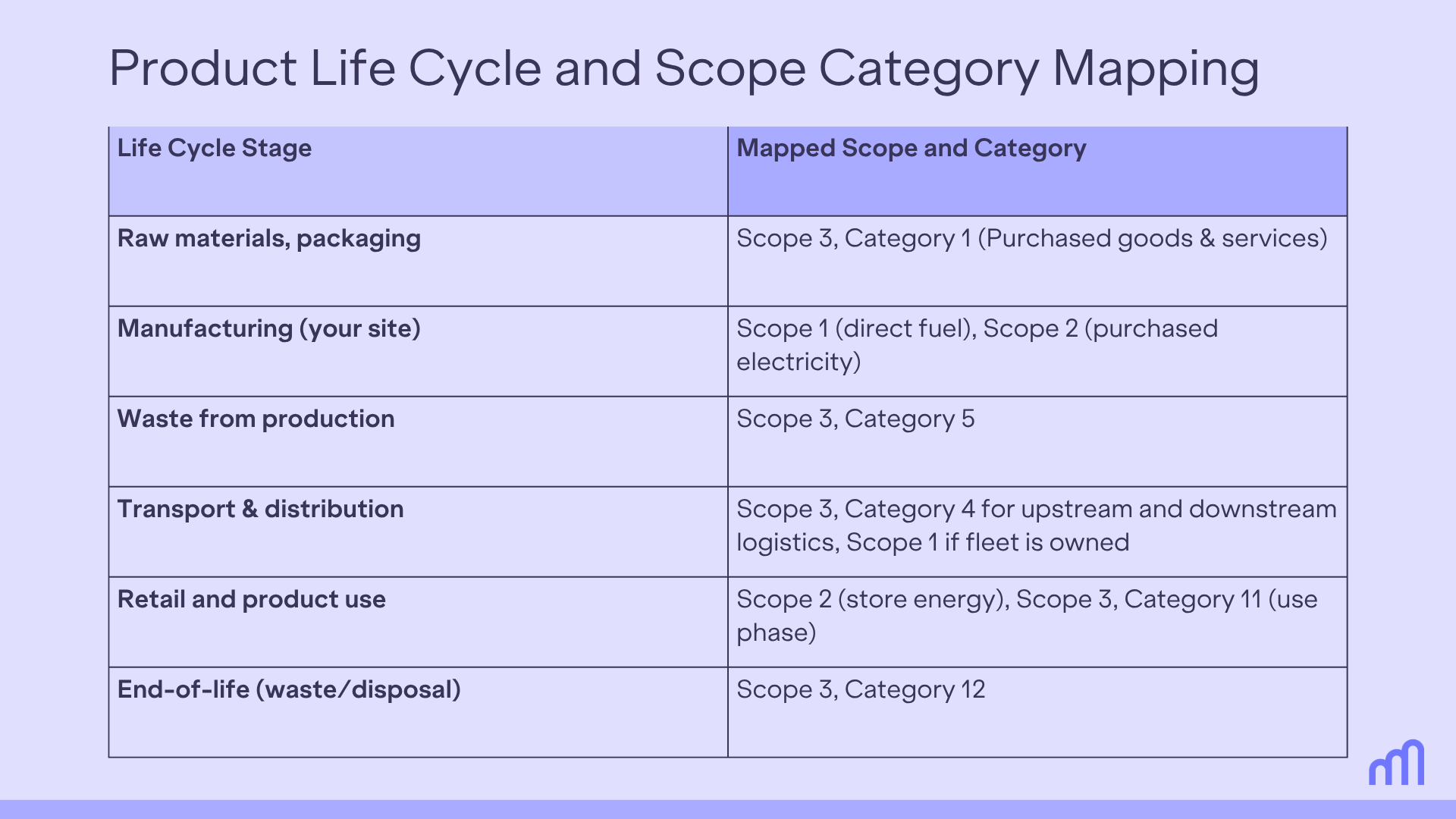

You also need to be clear about system boundaries. Are your PCFs cradle-to-gate (ending at the factory gate) or cradle-to-grave (including use and disposal)? This affects how each PCF maps to Scope 1, 2, or 3.

For example:

To integrate PCFs into your CCF, multiply each product’s PCF by the number of units sold or produced during the reporting year.

For example:If one jar of tomato sauce has a PCF of 0.5 kg CO₂e, and you sold 10 million jars, that product contributes 5 million kg CO₂e to your corporate footprint.

Repeat for each product with available PCF data, then map the totals to the appropriate Scope 3 category, usually Category 1: Purchased Goods and Services.

Avoid counting the same emissions twice. If a product’s footprint includes emissions from your own operations (e.g., factory energy use), don’t also report those under Scope 1 or 2.

The same applies within Scope 3. If you combine product-level data with supplier-level or spend-based estimates, clearly define where the data overlaps. For example, if a supplier’s footprint is included in your PCF, you shouldn’t also count that supplier’s emissions separately under Category 1.

To report correctly, you need to link each part of the product’s life cycle to the right emissions category.

Use a carbon accounting platform (or an internal system) to store PCF data and track how it feeds into your CCF. This helps with documentation, year-over-year comparisons, and preparing audit-ready reports.

Discover how Carbon Maps helps food companies trace emissions back to specific products and suppliers, so they know exactly where to reduce.